When video-streaming service Netflix released political thriller House of Cards in February 2013, executives already knew that millions around the world would be cancelling their weekend plans to binge-watch all 13 episodes of the show. But how?

The protagonist of the show, Francis Underwood—played by Kevin Spacey—would say something (in his signature Georgia drawl, of course) along the lines of, “Well, now, wouldn’t you like to know?”

Unlike Frank, we’re not opposed to telling you. The secret to Netflix’s success is Fast Data. Below are some of the ways Fast Data is changing the way we view TV, with House of Cards as the main character.

“Power is a lot like real estate. It’s all about location, location, location.” — Season 1

When Netflix put $100 million toward the first two seasons of the show, they were very well aware of the property value on which they were sitting. Customer sentiment—from more than 27 million viewers in the U.S. and 33 million worldwide viewers at the time—provided all the context for their decisions.

Netflix was able to determine that the show would be successful by acting on the insights they gleaned from the steady stream of user information that feeds constantly improving algorithms. They determined that viewers of the British version (which had already done well on the platform) rated Kevin Spacey’s films highly and watched David Fincher’s movies from beginning to end.

In fact, millions of times a day, Netflix is collecting data on browsing habits, including when you pause, rewind or fast forward, which day you’re watching a particular show, how many episodes you watch in a row, if you return to finish Breakfast at Tiffany’s after having paused it, or how you came to choose The Wolf of Wall Street (and how long it took you to make the decision).

Indeed, it turned out this understanding of their viewership worked. House of Cards was the first online-only show to win an Emmy. It has also been the most-watched show in every country where Netflix exists, and made back its $100 million investment—within three months of the first season being aired—by increasing its user base by two million in the U.S and one million in the rest of the world.

“I should have thought of this before. Appeal to the heart, not the brain.” — Season 2

To market the show, Netflix did not use the traditional 2-3 original trailers to entice the masses. Instead, they created 10 advertisements that targeted viewers from different angles, depending on their preferences as a customer. Netflix is always improving their understanding of customers and their business with real-time insight tools that—while implementing the Fast Data model—turn those insights (or analyses based on particular sets of data) into action.

For instance, if you’ve rated Kevin Spacey’s movies highly, the platform would know to put a trailer in front of you that featured the actor prominently. Perhaps you’re more inclined towards content in the Strong Female Leads section—you’d be shown a trailer featuring future FLOTUS Claire Underwood, played by award-winning actress Robin Wright. Or, perhaps, based on your most recent movie choices, Netflix deems that you are a film-junkie. You’d be seeing a particularly crafted trailer that showcases that David Fincher magic.

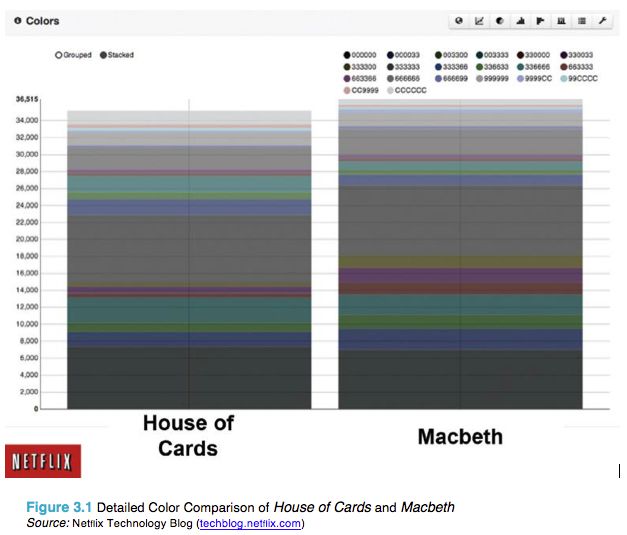

Correlations between choice and color are also a big focus for Netflix because it helps decide which kinds of covers are more likely to succeed in a given market. For example, when choosing a color scheme for the House of Cards cover, Netflix could determine that when people like a thriller with a certain color scheme, they’ll be attracted to another cover with similar intonations. This helps Netflix hedge their bets on creativity by interpreting the algorithms they compute. For example, see a side-by-side sample of Macbeth and the chosen colors of the House of Cards cover:

While Netflix doesn’t currently release ratings, we’re willing to reckon that viewership numbers were pretty high, considering the nearly 700,000 tweets referencing the show the weekend Season 3 came out. That, and its early foundation of using Fast Data in creative ways to pique the interest of viewers before they knew why they were interested in the first place.

“You have to respect your own mortality.” — Season 3

Analyzing data to make decisions in real time is how Netflix has been able to sustain constant new additions to their Netflix Originals. Orange is the New Black, Marco Polo, Tina Fey’s Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, and several more (actually, 320 hours of original programming in 2015, which is triple the amount from this past year) are all shows that we, as viewers, have led Netflix to believe will be a sure bet.

More often than not, they are right. Even when critics don’t enjoy an episode of Marco Polo, Netflix encourages them to compare their very close Rotten Tomatoes ratings to HBO’s Game of Thrones. Most of all, Netflix was right to gamble on the fact that viewers would want to watch original content from a company outside of the traditional network or movie studio environment that began as a simple DVD mail-order service. Just two years after their first foray into original content, Netflix expects to end the first quarter of 2015 with 61.4 million global subscribers.

The new normal of television has shifted and the lines between what we watch on an actual flat screen and what we watch on our computers no longer exist. Companies like Amazon, AT&T and HBO are getting into the betting cycle. HBO, despite vowing to never pursue streaming ventures outside of its cable roots, is launching a standalone service using Apple as its launch partner. This truly epitomizes customer data insights—and the ability to act on them—disrupting industries with well-established roots.

Indeed, the data-driven approach to movie- and TV-show-curation is not new. Netflix has been using data analysis for years to decide which content to license (don’t you ever wonder why only certain James Bond movies are available at a certain point in time?). They also use their well-established recommendation algorithms that help you decide what to watch next. But, without utilizing the Fast Data approach, a service like Netflix—or any network for that matter—couldn’t possibly know whether $100 million for a season is a good bet or a flop. This year, we’ll be able to watch Fast Data at work and we’re willing to bet Netflix will get the majority vote.